Autism in Adulthood: Beyond the Checklist

Many adults meet cut-offs for autism through an online quiz. The score may lead them to believe they are autistic. But as Dr. Vanessa Bal puts it, “a single score might mislead you.” Her talk at the NJACE & RUCARES Annual Conference argued for a simple shift with a big impact: don’t treat adulthood as one stage, and we need to go beyond surveys if we want to understand and diagnose autism in adults.

The core idea

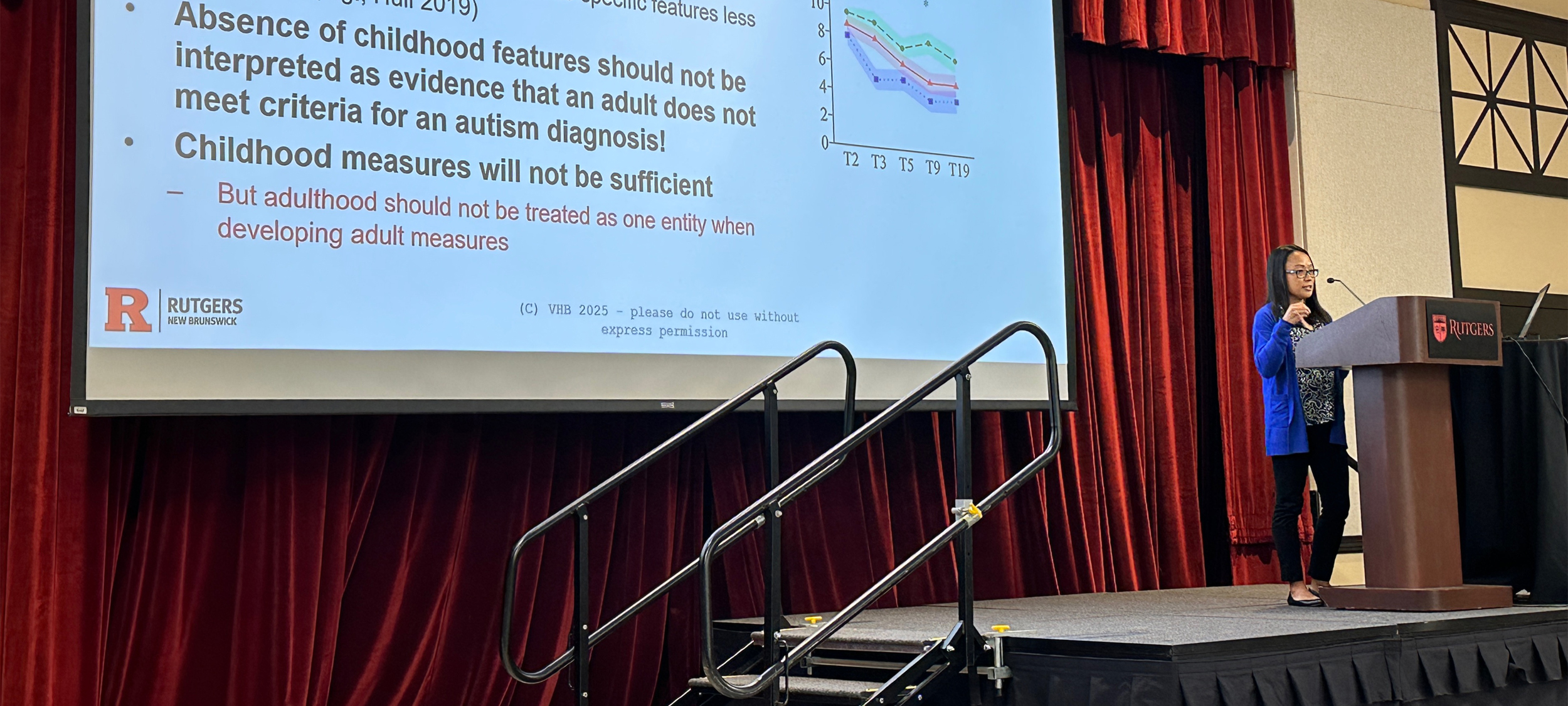

“Adulthood is not a single time point.” Autism can look different at 18, 40, and 60 because people change. Life experience, supports, and brains continue to develop and change. Yet much adult research focuses on 18–25-year-olds but is generalized to all adults. We likely miss key differences about middle and later-adulthood that are needed to inform supports.

At the same time, many popular tools intending to measure autistic features capture mood, attention, and context. Dr. Bal asked, “What are we actually measuring?” Preference items like “I’d rather go to the library than a party” can reflect personality, anxiety, or language differences, not autism itself. Her data show that depression and anxiety can inflate scores on common autism questionnaires. In other words, high scores can signal difficulties or distress, that may or may not be related to autism.

Why this matters

Two adults can land the same “autism score” for very different reasons. One might be autistic. Another might be facing untreated depression or ADHD. If we rely on checklists alone, we can miss what drives the behavior. This can result in mistaken referrals or misdiagnosis. As Dr. Bal noted, this is also important for animal researchers to consider because what matters is“ not the behavioral analog of what you can observe, but what is actually driving those behaviors underneath.”

Diagnostic timing also matters. Adults diagnosed later in life often have fewer obvious childhood delays yet report more co-occurring conditions. They also may not have had access to special education or other supports earlier diagnosed individuals had. Many seek a diagnosis for self-understanding, community, or clarity in relationships. Services can be limited, but a precise evaluation still guides better next steps.

A better way to evaluate

Dr. Bal’s solution is practical:

- Treat adulthood as a lifespan. Compare 20s, 40s, and 60s separately when possible.

- Separate childhood-diagnosed and adulthood-diagnosed adults in studies.

- Measure co-occurring conditions directly. Anxiety, depression, and ADHD symptoms may impact day-to-day life and influence scores on autism measures.

- Do not only focus on difficulties. Look for strengths and other positive qualities to understand variability in autism.

- Add observation. Short, structured interactions and standardized tasks may clarify what checklists blur.

The bottom line: A single score at one time point cannot capture autism in a meaningful way. Or in Dr. Bal’s words, “We have to move away from thinking about adulthood as a single stage or autism as a single dimension that can be described by a number.”

Sources

- NJACE & RUCARES Annual Conference, September 16, 2025, Rutgers University — Talk by Vanessa H. Bal, PhD (user-provided transcript).

Support better adult autism research and care

Help Rutgers Brain Health Institute advance lifespan-focused, strengths-based assessments and real-world tools beyond checklists.